Why we remain so stuck in the inadequate old system of public education has been answered in a number of ways. Deborah Meier in David Cayley’s 1999 CBC Educational Debates spoke of a lack of thoughtfulness for the long-range consequences of school reforms. She described educational leaders as “filled with a kind of chutzpah” who thought, “I know what’s right, I’m sure what world-class citizenship means, and, therefore, I have the right to impose it upon everybody else.”

John Gatto in his acclaimed book Dumbing Us Down put more weight on incompetence than arrogance when he said, “It is the great triumph of compulsory government monopoly mass-schooling that among even the best of my fellow teachers, and among even the best of my students’ parents, only a small number can imagine a different way to do things.” Marshall McLuhan’s comment echoes Gatto’s view: “We don’t know who discovered water, but we know it wasn’t the fish,” implying that those who have spent their lives swimming in the stagnant waters of public education have no idea that there is fresh water to be had.

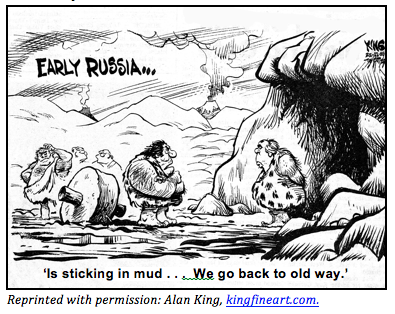

The Alan King’s cartoon well conveys another explanation. The conservative nature of the teaching profession has people scurrying back to old practices when reforms run into trouble. The concerted problem solving that goes into perfecting any new idea is rarely found in public education. There is seldom even a serious postmortem done when something that was thought would work – fails.

The Alan King’s cartoon well conveys another explanation. The conservative nature of the teaching profession has people scurrying back to old practices when reforms run into trouble. The concerted problem solving that goes into perfecting any new idea is rarely found in public education. There is seldom even a serious postmortem done when something that was thought would work – fails.

Politics is another culprit. Political timelines do not align with scientific ones. Governing parties need reforms to work before next elections, and so change is rushed. When reforms run into trouble, opposition parties use the situation to discredit the governing party and often the reforms are thrown out when there is a change in government.

It has been said that the most appropriate people to fix a problem are not the ones who created it in the first place. Thomas Kuhn who coined the term “paradigm shift” said it is often the young and the new to a field who usher in change. To fix public education, innovative students and educators need to be unleashed, freed from political agendas, and given ample opportunity to do the kind of research and development essential to refining even the best of ideas. For the sake of students and the futures of us all, let’s not confirm the view of those who say “science changes when old scientists die.” Public education needs to change now.